Bessemer Venture Partners’ Alex Ferrara takes a look at trends and predictions for the cloud industry in 2019. One of the most popular sessions from SaaStr Annual, this presentation will provides an in-depth look at the cloud computing industry across Europe and globally.

Want to see more content like this? Join us at SaaStr Annual 2020.

Alex Ferrara | Partner @ Bessemer Venture Partners

FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOW

Please welcome Bessemer Venture Partners’ Alex Ferrara to the stage.

I’m really super excited to be here today. I am really passionate about cloud, so are my partners at Bessemer. It’s great to be in a room with other people that are also really passionate about cloud, and we have participated in SaaStr I think five times now, and yet this is the first time we’re doing SaaStr Europa, so I’m really pumped about the opportunity to present to you today, and, personally, I’m really interested in this topic because, while I’m based in the US, I would say about half of my investments have some tie to Europe, and the reason for that is I have a personal, deep conviction that Silicon Valley and the Bay Area have no monopoly on innovation, and we have been seeing and I think we’ll continue to see great founders, great innovative companies, great, enduring companies emerge from around the world, from Europe and elsewhere, and so it’s my privilege to be here today and talk to you through or present to you our state of the cloud Europa edition.

What I’m going to do is talk a little bit about what we’ve seen over the course of the last year and then also talk about some metrics we track or we encourage our founders to track as they’re building their businesses, and then, lastly, try to go through a few predictions for the next couple of years. We’re going to do Q&A also via Slido, and there’s a link that they’re going to flash up here that you can use if you want to submit questions, so there it is. All right, so let’s dive in.

The first thing I want to do is actually quickly take you back a little bit to a time before SaaStr. A little more than 10 years ago, we released our 10 Laws of Cloud Computing, and it was done at a conference that was a lot smaller than this one in a room of probably 50 or 60 of the leading private and public cloud CEOs and founders at that time, and the question I’d pose to you is, at that time, is how many billion-dollar companies, billion-dollar private unicorns do you think were in existence at that time? Does anyone have a guess? How many unicorns were there?

The first thing I want to do is actually quickly take you back a little bit to a time before SaaStr. A little more than 10 years ago, we released our 10 Laws of Cloud Computing, and it was done at a conference that was a lot smaller than this one in a room of probably 50 or 60 of the leading private and public cloud CEOs and founders at that time, and the question I’d pose to you is, at that time, is how many billion-dollar companies, billion-dollar private unicorns do you think were in existence at that time? Does anyone have a guess? How many unicorns were there?

We’ve got a couple zeros, maybe a one, and you’re absolutely right, so, at that time, there were zero unicorns, and it probably shouldn’t be a surprise because, in the entire history of cloud computing at that point, there had been exactly zero companies that had managed to achieve $1 billion or better valuation in the private markets, and I make this point because I want to illustrate how far we’ve come, and I want to do that with the next question, which is how many billion-dollar private cloud companies do you think there are today, so, 10 years later? Maybe by a show of hands, raise your hand if you think there are more than 10 unicorns.

All right, keep them up. You think there are more than 20 unicorns? How about 40 unicorns? I see a few hands going down. 50? A few more. 60? Does anyone think there are more than 60? All right, so the answer is there are actually 61 a cloud unicorns, and we’ll flash them up. Many of these are names that you know, and this is actually the largest we’ve seen in history. I think it’s a really staggering stat.

Before I joined the venture capital industry many years ago, I was a software developer, and I worked for a startup around the 2000 time period. I think about this stat today, and I just remember working at a startup as a co-founder and thinking how fantastic would it be if we could scale that business and, ultimately, go public at $1-billion valuation, and what’s amazing to me is that, these days, a $1 billion is often a healthy Series C round on the way to an IPO, so the market really has grown quite a bit. The cloud software industry has changed. It’s not just the number of unicorns.

I think it’s also very telling when you think back 10 years ago to a time when Amazon was actually still a retail business. This is one of my favorite tweets as of late. It was around that time about 12 years ago that Jeff Bezos launched AWS, and some of you may remember that, when he did this, Wall Street analysts were looking at him and saying, “Why would you take what’s already a very unprofitable business and drive it further into the red by investing in this AWS initiative?” and what’s amazing to see is that, now, 12 years later, their… AWS is really what’s driving their business, so this analyst, Ari Levy from CNBC, took the Amazon earnings transcript from earlier this year and he actually counted the words, counted the number of times that words like AWS or retail or Alexa were mentioned. Retail was mentioned twice, that’s it, and AWS was mentioned 78 times, so it’s probably not surprising that they’re doing this.

If I was CEO of a company and I had two business lines, one of which was a low-margin retail business and the other which was a high-growth, high-margin cloud business, which one would I be promoting? Obviously, the cloud business, and so I think we’ve seen over the last decade that AWS now is arguably the biggest driver of value for Amazon as they are approaching this trillion-dollar market cap milestone, and the same goes for Microsoft. I think we’ve seen 10 years ago they were talking about desktop PC shipments and, more recently, Satya, who’s now the CEO, was appointed CEO, having run their cloud business, which is widely credited with allowing them to exceed the $1 trillion milestone in terms of market cap, so it’s no longer the case that the cool kids in the tech world are only the consumer Internet companies.

It used to be the Facebooks and the Airbnbs and so forth, and these days we’re seeing folks like our friend Tobi at Shopify , so, here, you have a German entrepreneur move to Ottawa, Canada, out of frustration with his attempt to sell… to start a snowboard shop selling snowboards online. He ended up building a small shopping cart that ultimately became this $30-billion market cap business that’s driven a massive amount of value, a massive amount of hiring along the way, and, also, I think it’s another example of great, enduring companies that are being founded and built outside of Silicon Valley.

, so, here, you have a German entrepreneur move to Ottawa, Canada, out of frustration with his attempt to sell… to start a snowboard shop selling snowboards online. He ended up building a small shopping cart that ultimately became this $30-billion market cap business that’s driven a massive amount of value, a massive amount of hiring along the way, and, also, I think it’s another example of great, enduring companies that are being founded and built outside of Silicon Valley.

Fast forward a little bit to some of the statistics that we’ve seen over the last year that also give us confidence that this cloud trend is real and persistent, this is the number or the amount of M&A that we saw in 2018, and most of this M&A activity has really been the legacy vendors buying their way into this cloud wave, so Red Hat, one of the largest M&A deals in the cloud space last year, acquired by IBM. IBM was in a situation where they were really jammed. They had fallen behind this latest wave of cloud innovation, and they had to acquire Red Hat in order to execute against their hybrid cloud vision, a similar story with SAP buying Qualtrics, Microsoft buying GitHub. We also saw Blackberry, which is one of the old guard companies buying Cylance for about a billion and five, and, actually, more recently, just in the last week, we saw Google acquire Looker for 2.6 and, now, Salesforce buying Tableau, so that trend has continued.

In the public markets, a very similar story, these are… This is 61 billion that was added in around the last 17 months. 2018 saw about $44 billion of value added to the public markets, companies like Dropbox, companies like DocuSign, and that has continued now into 2019. So far this year, we’ve seen PagerDuty. We’ve also seen Zoom, which had a fantastic IPO and has more than… almost doubled since its IPO to about a $26-billion market cap, and just yesterday, CrowdStrike, I think many of you know went public and also increased by something like 70% or 80% from its IPO price, and we also have other companies in the pipeline now like Slack, which is imminently going to be doing its direct listing, and so we’re expecting that 2019 will likely either exceed or… sorry, rather meet or exceed the same metrics from the same stat from 2014… 2018 rather.

Another thing we look at to sort of take a look at the future is our Cloud 100. This is a group of companies that we’ve put together at Bessemer in partnership with Forbes, and it’s released each year in their September edition, and it’s a list of what’s put together through an independent judge assesses as the leading 100 top cloud companies, and these cloud companies as of recently command about $200 billion of value.

I think the reason this is important is two reasons. One, it’s notable that, just in the last year for the first time, the number of these private cloud unicorns exceeds that of the public ones, so we’ve got a really healthy backlog of companies, and it continues to build. The value beyond the top 100 is also increasing really dramatically, and so we think this is a really good leading indicator for the health of the industry that we’re all building together, so it’s been a great decade to be a stakeholder in a cloud business, whether you were a founder, an employee or an investor, but the question we get asked quite frequently is when is this going to end? How long can this last?

Now, I’m a venture capital investor. I love charts like this that are up into the right, but I’ve also been doing this long enough to know that the path to success is rarely a smooth, up into the right curve. It’s more often a very turbulent experience, and the reality also is it takes a long time to build these companies. The time that companies are staying private has been extending. It’s often much more than a decade to build one of these cloud unicorns, and so I don’t know when the current bull market is going to end. It may persist for the next several years. It may persist for the next several years. It may go away in the next few weeks, but I do know that, because it’s taking so much longer to build these companies, chances are that, if you’re a founder of one of these companies, you will hit an economic speed bump along the way, and it’s very likely that you’ll hit a more severe market correction, and sometimes you really can’t tell whether it’s a short-term blip or it’s longer, likely to be a longer-term correction.

Now, I’m a venture capital investor. I love charts like this that are up into the right, but I’ve also been doing this long enough to know that the path to success is rarely a smooth, up into the right curve. It’s more often a very turbulent experience, and the reality also is it takes a long time to build these companies. The time that companies are staying private has been extending. It’s often much more than a decade to build one of these cloud unicorns, and so I don’t know when the current bull market is going to end. It may persist for the next several years. It may persist for the next several years. It may go away in the next few weeks, but I do know that, because it’s taking so much longer to build these companies, chances are that, if you’re a founder of one of these companies, you will hit an economic speed bump along the way, and it’s very likely that you’ll hit a more severe market correction, and sometimes you really can’t tell whether it’s a short-term blip or it’s longer, likely to be a longer-term correction.

If you look more recently, in December of last year, that was the worst performing month for the NASDAQ in history, and then you contrast that with January, which was actually the best performing month in history, and then, last week, I think we had a five-day period where we had the best performing five days that NASDAQ had seen in seven and a half years, so the volatility is real and can be quite severe, and so what can smart founders do when they think about how to manage this volatility, how to build resilient companies, and so that’s really what I want to talk about now.

After hearing a lot of discussions about this topic at board meetings, we went off and we did some research. We tried to put together a framework that I’m going to walk you through that’ll help founders think through how to build a resilient company, and we’ve identified four key areas. They are all linked as we’ll see a little later on, but one of the first questions we often get from founders is what’s the right growth rate to target? What’s a mix of both realistic as well as, perhaps, a little bit aspirational as a growth rate that I should target in building my business?

What we did is we went out and looked at a sampling of the most successful public cloud companies, and we’ve listed a few of them here, and this shows the time it took these companies to go from a million of ARR to 100 million of ARR. Now, these are outstanding companies. Some of them represent really the cream of the crop. If you look at Slack, and I recognize they’re not a public company, but we’ve included them because they’re… Imminently, they will be. They got to 100 million of ARR from 1 million in three years, which is just incredible. I think that’s probably the fastest we’ve ever seen a company get to that scale.

If you contrast that, on the right side, companies like BlackLine, also a very successful company, a multi-billion-dollar public company, it took them about 13 years to get to this level, so as we dig a little bit deeper into the data, we decided to take the dataset and segment it, and we looked at the performance of the median, the top quartile and the bottom quartile in this set of successful companies, and what we see is the median company, the median successful cloud company, is getting to this 100-million mark in about 7.3 years.

The best companies or the top quartile companies are doing it in a little over five years, and the bottom quartile, it’s usually taking them a little bit more than 10 years, so it’s informative, it’s interesting, and yet 10 years is a very long time, and most of my focus at Bessemer is early-stage investing, and I would suspect that most of the people in this room as founders are also early-stage entrepreneurs, so the natural question that gets raised is how do I know whether I’m tracking from an earlier stage? If I’m at a million of ARR or 5 million of ARR, how do I know whether I’m on track to ultimately build one of these cloud companies, these unicorn cloud companies?

The next thing we did is we put together this BVP growth benchmark to understand how your company is tracking and we looked again at the data from both, a large dataset of both public and private companies, and so what we see here is this question of how long does it take to get from… Among the companies in each of these buckets that achieved this 100-million mark, how long did it take them to go from a million to 10 million of ARR?

Starting with the companies in the good bucket, so what does good look like? Achieving 10 million of ARR in four years puts you in the good bucket, and this implies a growth rate of about 80% per year over that time period. These are companies like Blackstone. They’re companies like Cornerstone OnDemand, so it’s no small feat to grow your business at 80% year-over-year for four years, but if you’re able to do that, you’re in very good company.

The better companies will achieve the same in about three years, and so that implies a growth rate of about 115% year-over-year, and the pattern we saw in these companies was not so much a linear growth rate, but, more frequently, they’re going from 1 million to 3 million and then roughly doubling for each of the next two years. A good example of that was Coupa Software in its earlier days, and then the best companies that are getting to 10 million in two years, these are companies that are growing at around 215% year-on-year. They’re doing a little bit more than tripling, so an example of that company would be a Twilio, so, if you’re looking to build a cloud unicorn or if you’re looking to build a successful, enduring cloud company, hopefully, this gives you a little bit of a better sense for whether you are tracking at the earlier stages of the company’s evolution.

We talked about growth. The next topic in our framework is retention, so, once you’ve acquired these customers and you start to scale the business, how should you think about the investment needed to retain those customers? I would argue that retention is probably the most important of these categories, so the first thing to note is that retention is really going to differ, depending on your market segment. If you’re selling into the mid-market with ACV of something like 12K or up to 50K per year, you can expect 80 to 90% gross revenue retention; and, net revenue retention, we typically see something in the 90 to, in best cases, 120%.

Contrast that with companies that might also sell into the SMB segment of the market where the ASPs, the average deal sizes are lower. SMB businesses just go out of business much more frequently, and so their gross retention numbers are going to be lower. In fact, I think the annual rate of SMB failure is about 10%, and so that’s why the gross retention rates are about 10 percentage points lower in that SMB segment.

Now, it’s important to realize that the churn is higher, retention is lower, the average deal sizes are lower, and so obviously you can’t spend as much to acquire those customers if you want to maintain the same lifetime value to CAC for each of these segments, and, again, if you contrast it with the enterprise segment of the business, these are deals that often are a 100K ACV, maybe even $1 million or more. We generally see that these companies, these deals, it’s far more expensive. Usually, it requires an outbound sales motion. It’s far more expensive to acquire these customers, but they stick around, and the retention can be, as we’ll see a little bit later, much, much higher.

I want to just run through a quick example to drive home how important retention is as a driver of value in your company, and so I’m going to use this example of a company that manages to get to or scales to 200 million in revenue, and this company has a net retention of 110%, and we’re going to assume it’s valued at a 10X revenue multiple, which is around where the market is trading today, so the company value is about $2 billion, so let’s pretend for a second that this company earlier in its life made the decision to invest heavily in customer success and they were really able to drive up that net retention by 15%, bringing it to 125%. That additional 15% of net retention translates to $1.5 billion of additional value for the company, and that’s because this net retention compounds over time.

In fact, each, in this particular example, each 1% of additional retention translates to $100 million of value at the time the company exits, and, also, what’s not shown here is that higher net retention not only allows them to get to greater scale, but to exit with a faster growth rate because they’re not having to add as many new customers on the… at the top of the funnel, so, if you contrast this with the flip side, where we have a company where retention drops by 10% from our base case example, this lower retention unfortunately compounds in the opposite direction, and this company loses about 630 million of value, so what’s the lesson? Invest in customer success. I’d say track retention. Typically, you’d like to track net promoter score or some similar metric, NPS, as a means, a leading indicator to determine the health of your customers, and, also, in doing so, I think, as we can see, it creates a massive amount of value.

I’d also point out that, when you think about our prior topic of ARR growth and net retention, for the same amount of investment in each of those areas, I think we tend to find that you get a lot more bang for your buck when you invest in net retention rather than investing in net new customer ads, and that’s because one of the really beautiful things of the SaaS business model is that you get a tremendous amount of end user telemetry. You know how many seats your customers are using, how frequently they’re using them, when they churn, what features they’re using and so forth.

There’s just a massive amount of data that’s available, and the companies that early on are really able to understand that and to try to take it in and optimize it are able to really move the needle quite nicely in this area, and unlike adding new customers, you know a lot about your existing customers, you may not know much at all about the customer prospect side of your business, and so I think we find this is often an easier or a more efficient area to optimize.

Two examples, or maybe I should say now one example since SendGrid and Twilio have merged, of great net retention are here, so each of these companies started off in the early days with very much a bottoms-up go-to-market motion. It was very marketing-driven, going after the SMB segment and the mid-market segment and then, over time, really figuring out how to penetrate the enterprise segment with much higher ACVs, and so, as we’ll see later, it really resulted in a tremendous success for these companies which I think are now valued at close to $20 billion in the public markets.

The third tactic I wanted to quickly talk about is cash in the bank, so, now, we figured out… We talked about growing your customers. We talked about how to retain them, so how do you raise the capital that you need to scale that operation of adding ARR and improving your retention?

We like to recommend that you manage your runway and you buffer for contingency. A lot of things can happen. Out of the blue, you can face product launches that are late, competition arises, price commoditization, maybe it becomes more expensive to acquire customers, so it’s really helpful to make sure you always have a buffer, and we tend to recommend that you raise financing that’ll last you between 18 and 24 months of runway.

The last point here is that hiring can really be a big lever. In these SaaS businesses, your people are most likely your greatest asset. They’re also likely your greatest cost base, and so investing in… hiring and investing in HR and then also, on the other side, being really careful about making changes quickly when needed can really help with managing runway.

You can’t talk with a founder without talking about financing. Our recommendation is that you think one financing ahead. This example here is showing you market multiples over the last several years, and I think what you see here is that it’s been very volatile, and if you had raised your capital, your round of financing in March of 2004, you might benefit or have been rewarded by that 10X multiple, but if you missed and it took you two months longer to close that financing, all of a sudden, you’re in a market environment where multiples have dropped by 40%, and maybe your investor isn’t going to re-trade, but it’s an uncomfortable position to be in when you’re negotiating those definitive documents and the market is tanking.

Similarly, if you had raised in 2014 and then your next time of raising is this February, 2016, when the multiples had cut in half, you could have a company that has doubled in size by that point in time, but if the multiples are now half, maybe you’re raising money at around the same level, and so I think that’s one of the reasons why we’ve been seeing so many companies raise money six months after their last financing because they want to make sure they have ample runway so that they don’t run into one of these scenarios.

The last tactic I want to talk about is efficiency, and this is the question of how do you balance the prior three? How do you figure out how much to spend and when? There’s a metric that many of you may be familiar with called the Rule of 40. This Rule of 40 is something that is applicable for measuring efficiency of later-stage companies, usually public market companies or later-stage growth companies. It is ARR growth plus your free cash burn. If you’re not familiar about it… familiar with it, don’t worry about it, but I mentioned it because we found that it’s not really as relevant for earlier-stage companies.

Companies below 30 million of ARR, we tend to find that a much better way of measuring efficiency is through looking at this score of net new ARR divided by cash burn, and so why is this important? The reason why this is important is that I think we found that, in bull markets, investors reward growth, and they may not care at all about how much cash burn is required to get there. In fact, we’ve seen time and time again that high ARR growth companies often have premium valuations when the market is really hot, but, in all other market conditions, if it’s flat, if it’s down, the market rewards efficiency, and so we generally recommend that you really focus on efficiency instead of ARR so that, when the market does turn, you’ll still be rewarded, and so what’s a good efficiency score?

Again, having gone through a large dataset, we typically saw that something between 0.5X and one-and-a-half X representative a very good score, and some of the best companies we see have scores above that. One example I’ll give, one of the best companies out there on this metric was Shopify, which is a company that in around 2011 had about 12 million of ARR. Over the next 12 months, they added another 12 million of ARR, and it cost them 2 million to do that, so a 6X efficiency score, which is really putting them in the best-in-class category.

In summary, we think these are the four metrics you should track if you want to build a resilient company. We’ve referred to them as GRIT. We think it’s a powerful framework for helping to manage and measure the resilience of your business, and one of the things we find is you can also add them together and, in doing so, we generally found that if you can achieve a GRIT score between three and six, you’re in very good company.

In summary, we think these are the four metrics you should track if you want to build a resilient company. We’ve referred to them as GRIT. We think it’s a powerful framework for helping to manage and measure the resilience of your business, and one of the things we find is you can also add them together and, in doing so, we generally found that if you can achieve a GRIT score between three and six, you’re in very good company.

Now, one of the things I want to leave you with is there are a number of ways to do this. You can over-index and under-index in different of these areas and still have a very resilient business. One of the examples I like to give again is Twilio. Here’s a company that really over-indexed on annual net retention. They had 160% annual net retention. They were growing at around 300% per year when they were at this scale, and so, with two years of cash in the bank and a 1.5X efficiency score, their GRIT score was 8.1, which was very strong.

Another example that over-indexed in a different way is ServiceTitan. ServiceTitan over-indexed on efficiency with a 3.4X score. They under-indexed a little bit on net retention at around 90%, so, with 200% growth and, again, two years of cash in the bank, they had a very similar GRIT score of about 8.3, so there are multiple ways to… multiple paths to success, and that’s one of the points I want to leave you with. I think these metrics hopefully will be helpful as you think about how to build a resilient company.

Now, all the metrics are valuable, but I think what often would overshadow these is the fact that you got to figure out where you’re going to build your company to begin with, and so I want to just take a couple of minutes and talk about some of the predictions that we have internally for where to… where we’re going to see opportunity going forward, so, this last section, I just want to take a few minutes and talk about where we see the opportunity over the next several years.

At BVP, as investors, we put our money where our mouth is, and these are in fact five of the areas where we’re spending a lot of time looking, either we’ve made investments recently or we’re looking to make investments now. I suspect this will resonate with many of the people in this room because, presumably, you’re also thinking about starting companies in these areas or you’ve already done so or you’re thinking about launching a new product line or you’ve already done so.

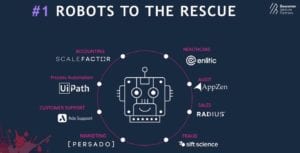

The first I want to talk about is this theme of robots to the rescue.  You hear a lot about worker displacement by AI and machine learning, and we really see the other side of it, which is that the combination of advances in AI and machine learning, when paired with a human, has the potential to really give them superpowers in a very meaningful way in a range of different industries, and we think that it’s particularly pronounced in industries where you have really massive datasets like fraud or financial transaction data or customer support or marketing, and these are areas where it’s often too difficult for human on their own to rationally process the data, but when paired with the right mix of AI and machine learning, we think they can do a far better job than either a machine alone or a human alone, and so this is one of the areas where we’re finally seeing in a very tangible way across many markets, Sift Science in fraud and ScaleFactor in financial, we’re seeing this work, and we think this trend is really just getting started.

You hear a lot about worker displacement by AI and machine learning, and we really see the other side of it, which is that the combination of advances in AI and machine learning, when paired with a human, has the potential to really give them superpowers in a very meaningful way in a range of different industries, and we think that it’s particularly pronounced in industries where you have really massive datasets like fraud or financial transaction data or customer support or marketing, and these are areas where it’s often too difficult for human on their own to rationally process the data, but when paired with the right mix of AI and machine learning, we think they can do a far better job than either a machine alone or a human alone, and so this is one of the areas where we’re finally seeing in a very tangible way across many markets, Sift Science in fraud and ScaleFactor in financial, we’re seeing this work, and we think this trend is really just getting started.

A second area that I want to talk about is one where Europe is clearly leading the way, and that’s consumer privacy protection, and GDPR has been a big catalyst here over the last year. We’ve seen in the US regulations like CCPA, which are likely to happen next year or have been approved to happen next year, but the problem we think of consumer privacy is far broader than the regulations. We’ve seen a growing volume of enterprise data breaches and mishandling of consumer data. The most publicized one probably is Facebook and the Cambridge Analytica scandal, and yet we’ve seen this across many verticals and many industries, and it’s only getting more frequent and more severe, and I don’t think this is a problem that’s going to be solved by cybersecurity tools. I think that this is a problem that results from poor privacy engineering on the part of SaaS application companies over the last decade, and so we’re looking at companies that can help address this problem.

We think that there has been a buildup of massive amount of what I call privacy technical debt. As many of these companies have taken in too much data, they don’t have the right processes for handling and so forth, so, in the near term, we think there are opportunities for companies that help enterprises manage consumer privacy, and then longer term, as we see more enterprises focus on AI and machine learning as a key part of their growth strategy, we think the public is likely not going to support situations where these companies are using Black Box AI systems that may or may not have internal biases either in the algorithms or in the datasets, and so we think there’s going to be a shift towards what we call responsible AI or ethical AI which are less opaque, more transparent, so we’re looking at tools and techniques that help get the value from AI and machine learning, but do so in an ethical and transparent way.

I’m going to flip through because I’m know I’m out of time, and I’m happy to talk about any of these areas afterwards unless… I don’t know if we have a couple more… Maybe I will flip through and see if folks have questions because I know that people may have submitted some.

Verticalization of mobile and mobile applications is another big area of focus, also very focused on low code and no code environments, which is really at the intersection of these API-driven developer-first businesses and the first wave of application software businesses, and so those are our five predictions, so, when you pull it all together, if the last decade has seen now almost a trillion dollars of value created in the cloud, we think these five areas are likely to create the next trillion dollars of value.

These journeys are rarely without turbulence, and so I hope the GRIT framework that we provide is valuable as you think about scaling your companies, and, of course, the most critical ingredients are always the founders and the teams which, when put together, are really able to, in combination with these market trends, amplify the outcomes, so we’re really excited to be a part of your next company, your next adventure, and thank you for having us here today.